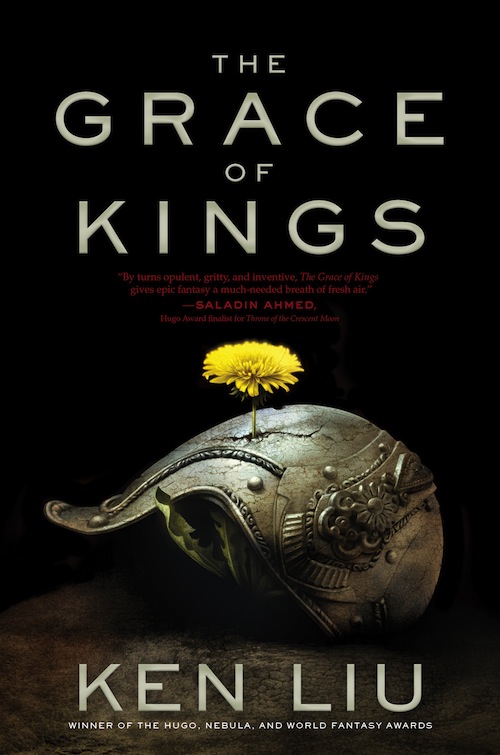

Two men rebel together against tyranny—and then become rivals—in The Grace of Kings, the first sweeping book of an epic fantasy series from Ken Liu, available April 7th from Saga Press.

Wily, charming Kuni Garu, a bandit, and stern, fearless Mata Zyndu, the son of a deposed duke, seem like polar opposites. Yet, in the uprising against the emperor, the two quickly become the best of friends after a series of adventures fighting against vast conscripted armies, silk-draped airships, and shapeshifting gods.

Once the emperor has been overthrown, however, they each find themselves the leader of separate factions—two sides with very different ideas about how the world should be run and the meaning of justice.

Chapter One

An Assassin

Zudi: The Seventh Month in the Fourteenth Year

of the Reign of One Bright Heaven.

A white bird hung still in the clear western sky and flapped its wings sporadically.

Perhaps it was a raptor that had left its nest on one of the soaring peaks of the Er-Mé Mountains a few miles away in search of prey. But this was not a good day for hunting—a raptor’s usual domain, this sun-parched section of the Porin Plains, had been taken over by people.

Thousands of spectators lined both sides of the wide road out of Zudi; they paid the bird no attention. They were here for the Imperial Procession.

They had gasped in awe as a fleet of giant Imperial airships passed overhead, shifting gracefully from one elegant formation to another. They had gawped in respectful silence as the heavy battlecarts rolled before them, thick bundles of ox sinew draping from the stone-throwing arms. They had praised the emperor’s foresight and generosity as his engineers sprayed the crowd with perfumed water from ice wagons, cool and refreshing in the hot sun and dusty air of northern Cocru. They had clapped and cheered the best dancers the six conquered Tiro states had to offer: five hundred Faça maidens who gyrated seductively in the veil dance, a sight once reserved for the royal court in Boama; four hundred Cocru sword twirlers who spun their blades into bright chrysanthemums of cold light that melded martial glory with lyrical grace; dozens of elegant, stately elephants from wild, sparsely settled Écofi Island, painted with the colors of the Seven States—the largest male draped in the white flag of Xana, as one would expect, while the others wore the rainbow colors of the conquered lands.

The elephants pulled a moving platform on which stood two hundred of the best singers all the Islands of Dara had to offer, a choir whose existence would have been impossible before the Xana Conquest. They sang a new song, a composition by the great imperial scholar Lügo Crupo to celebrate the occasion of the Imperial tour of the Islands:

To the north: Fruitful Faça, green as the eyes of kind Rufizo,

Pastures ever kissed by sweet rain, craggy highlands shrouded in mist.

Soldiers walking next to the moving platform tossed trinkets into the crowd: Xana-style decorative knots made with bits of colorful string to represent the Seven States. The shapes of the knots were meant to evoke the logograms for “prosperity” and “luck.” Spectators scrambled and fought one another to catch a memento of this exciting day.

To the south: Castled Cocru, fields of sorghum and rice, both pale and dark,

Red, for martial glory, white, like proud Rapa, black, as mournful Kana.

The crowd cheered especially loudly after this verse about their homeland.

To the west: Alluring Amu, the jewel of Tututika,

Luminous elegance, filigreed cities surround two blue lakes.

To the east: Gleaming Gan, where Tazu’s trades and gambles glitter,

Wealthy as the sea’s bounty, cultured like the scholars’ layered gray robes.

Walking behind the singers, other soldiers held up long silk banners embroidered with elaborate scenes of the beauty and wonder of the Seven States: moonlight glinting from snowcapped Mount Kiji; schools of fish sparkling in Lake Tututika at sunrise; breaching crubens and whales sighted off the shores of Wolf’s Paw; joyous crowds lining the wide streets in Pan, the capital; serious scholars debating policy in front of the wise, all-knowing emperor.…

To the northwest: High-minded Haan, forum of philosophy,

Tracing the tortuous paths of the gods on Lutho’s yellow shell.

In the middle: Ring-wooded Rima, where sunlight pierces ancient

Forests to dapple the ground, as sharp as Fithowéo’s black sword.

Between each verse, the crowd bellowed out the chorus along with the singers:

We bow down, bow down, bow down to Xana, Zenith, Ruler of Air,

Why resist, why persist against Lord Kiji in strife that we can’t bear?

If the servile words bothered those in this Cocru crowd who had probably taken up arms against the Xana invaders scarcely more than a dozen years ago, any mutterings were drowned out by the full-throated, frenzied singing of the men and women around them. The hypnotic chant held a power of its own, as if by mere repetition the words gained weight, became more true.

But the crowd wasn’t close to being satisfied by the spectacle thus far. They hadn’t seen the heart of the Procession yet: the emperor.

The white bird glided closer. Its wings seemed to be as wide and long as the spinning vanes of the windmills in Zudi that drew water from deep wells and piped it into the houses of the wealthy—too big to be an ordinary eagle or vulture. A few spectators looked up and idly wondered if it was a giant Mingén falcon, taken more than a thousand miles from its home in faraway Rui Island and released here by the emperor’s trainers to impress the crowd.

But an Imperial scout hidden among the crowd looked at the bird and furrowed his brows. Then he turned and shoved his way through the crowd toward the temporary viewing platform where the local officials were gathered.

Anticipation among the spectators grew as the Imperial Guards passed by, marching like columns of mechanical men: eyes straight ahead, legs and arms swinging in unison, stringed marionettes under the guidance of a single pair of hands. Their discipline and order contrasted sharply with the dynamic dancers who had passed before them.

After a momentary pause, the crowd roared their approval. Never mind that this same army had slaughtered Cocru’s soldiers and disgraced her old nobles. The people watching simply wanted spectacle, and they loved the gleaming armor and the martial splendor.

The bird drifted even closer.

“Coming through! Coming through!”

Two fourteen-year-old boys shoved their way through the tightly packed crowd like a pair of colts butting through a sugarcane field.

The boy in the lead, Kuni Garu, wore his long, straight, black hair in a topknot in the style of a student in the private academies. He was stocky—not fat but well-muscled, with strong arms and thighs. His eyes, long and narrow like most men from Cocru, glinted with intelligence that verged on slyness. He made no effort to be gentle, elbowing men and women aside as he forced his way forward. Behind him, he left a trail of bruised ribs and angry curses.

The boy in the back, Rin Coda, was gangly and nervous, and as he followed his friend through the throng like a seagull dragged along on the tailwind of a ship, he murmured apologies at the enraged men and women around them.

“Kuni, I think we’ll be okay just standing in the back,” Rin said. “I really don’t think this is a good idea.”

“Then don’t think,” Kuni said. “Your problem is that you think too much. Just do.”

“Master Loing says that the gods want us to always think before we act.” Rin winced and ducked out of the way as another man swore at the pair and took a swing at them.

“No one knows what the gods want.” Kuni didn’t look back as he forged ahead. “Not even Master Loing.”

They finally made it through the dense crowd and stood right next to the road, where white chalk lines indicated how far spectators could stand.

“Now, this is what I call a view,” Kuni said, breathing deeply and taking everything in. He whistled appreciatively as the last of the semi-nude Faça veil dancers passed in front of him. “I can see the attraction of being emperor.”

“Stop talking like that! Do you want to go to jail?” Rin looked nervously around to see if anyone was paying attention—Kuni had a habit of saying outrageous things that could be easily interpreted as treason.

“Now, doesn’t this beat sitting in class practicing carving wax logograms and memorizing Kon Fiji’s Treatise on Moral Relations?” Kuni draped his arm around Rin’s shoulders. “Admit it: You’re glad you came with me.”

Master Loing had explained that he wasn’t going to close his school for the Procession because he believed the emperor wouldn’t want the children to interrupt their studies—but Rin secretly suspected that it was because Master Loing didn’t approve of the emperor. A lot of people in Zudi had complicated views about the emperor.

“Master Loing would definitely not approve of this,” Rin said, but he couldn’t take his eyes away from the veil dancers either.

Kuni laughed. “If the master is going to slap us with his ferule for skipping classes for three full days anyway, we might as well get our pain’s worth.”

“Except you always seem to come up with some clever argument to wiggle out of being punished, and I end up getting double strokes!”

The crowd’s cheers rose to a crescendo.

On top of the Throne Pagoda, the emperor was seated with his legs stretched out in front of him in the position of thakrido, cushioned by soft silk pillows. Only the emperor would be able to sit like this publicly, as everyone was his social inferior.

The Throne Pagoda was a five-story bamboo-and-silk structure erected on a platform formed from twenty thick bamboo poles—ten across, ten perpendicular—carried on the shoulders of a hundred men, their chests and arms bare, oiled to glisten in the sunlight.

The four lower stories of the Throne Pagoda were filled with intricate, jewel-like clockwork models whose movements illustrated the Four Realms of the Universe: the World of Fire down below—filled with demons who mined diamond and gold; then, the World of Water—full of fish and serpents and pulsing jellyfish; next, the World of Earth, in which men lived—islands floating over the four seas; and finally the World of Air above all—the domain of birds and spirits.

Wrapped in a robe of shimmering silk, his crown a splendid creation of gold and glittering gems topped by the statuette of a cruben, the scaled whale and lord of the Four Placid Seas, whose single horn was made from the purest ivory at the heart of a young elephant’s tusk and whose eyes were formed by a pair of heavy black diamonds—the largest diamonds in all of Dara, taken from the treasury of Cocru when it had fallen to Xana fifteen years earlier— Emperor Mapidéré shaded his eyes with one hand and squinted at the approaching form of the great bird.

“What is that?” he wondered aloud.

At the foot of the slow-moving Throne Pagoda, the Imperial scout informed the Captain of the Imperial Guards that the officials in Zudi all claimed to have never seen anything like the strange bird. The captain whispered some orders, and the Imperial Guards, the most elite troops in all of Dara, tightened their formation around the Pagoda-bearers.

The emperor continued to stare at the giant bird, which slowly and steadily drifted closer. It flapped its wings once, and the emperor, straining to listen through the noise of the clamoring, fervent crowd, thought he heard it cry out in a startlingly human manner.

The Imperial tour of the Islands had already gone on for more than eight months. Emperor Mapidéré understood well the necessity of visibly reminding the conquered population of Xana’s might and authority, but he was tired. He longed to be back in Pan, the Immaculate City, his new capital, where he could enjoy his zoo and aquarium, filled with animals from all over Dara—including a few exotic ones that had been given as tribute by pirates who sailed far beyond the horizon. He wished he could eat meals prepared by his favorite chef instead of the strange offerings in each place he visited— they might be the best delicacies that the gentry of each town could scrounge up and proffer, but it was tedious to have to wait for tasters to sample each one for poison, and inevitably the dishes were too fatty or too spicy and upset his stomach.

Above all, he was bored. The hundreds of evening receptions hosted by local officials and dignitaries merged into one endless morass. No matter where he went, the pledges of fealty and declarations of submission all sounded the same. Often, he felt as though he were sitting alone in the middle of a theater while the same performance was put on every night around him, with different actors saying the same lines in various settings.

The emperor leaned forward: this strange bird was the most exciting thing that had happened in days.

Now that it was closer, he could pick out more details. It was… not a bird at all.

It was a great kite made of paper, silk, and bamboo, except that no string tethered it to the ground. Beneath the kite—could it be?— hung the figure of a man.

“Interesting,” the emperor said.

The Captain of the Imperial Guards rushed up the delicate spiral stairs inside the Pagoda, taking the rungs two or three at a time. “Rénga, we should take precautions.”

The emperor nodded.

The bearers lowered the Throne Pagoda to the ground. The Imperial Guards halted their march. Archers took up positions around the Pagoda, and shieldmen gathered at the foot of the structure to create a temporary bunker walled and roofed by their great interlocking pavises, like the shell of a tortoise. The emperor pounded his legs to get circulation back into his stiff muscles so that he could get up.

The crowd sensed that this was not a planned part of the Procession. They craned their necks and followed the aim of the archers’ nocked arrows.

The strange gliding contraption was now only a few hundred yards away.

The man hanging from the kite pulled on a few ropes dangling near him. The kite-bird suddenly folded its wings and dove at the Throne Pagoda, covering the remaining distance in a few heartbeats. The man ululated, a long, piercing cry that made the crowd below shiver despite the heat.

“Death to Xana and Mapidéré! Long live the Great Haan!”

Before anyone could react, the kite rider launched a ball of fire at the Throne Pagoda. The emperor stared at the impending missile, too stunned to move.

“Rénga!” The Captain of the Imperial Guards was next to the emperor in a second; with one hand, he pushed the old man off the throne and then, with a grunt, he lifted the throne—a heavy ironwood sitting-board covered in gold—with his other hand like a giant pavise. The missile exploded against it in a fiery blast, and the resulting pieces bounced off and fell to the ground, throwing hissing, burning globs of oily tar in all directions in secondary explosions, setting everything they touched aflame. Unfortunate dancers and soldiers screamed as the sticky burning liquid adhered to their bodies and faces, and flaming tongues instantly engulfed them.

Although the heavy throne had shielded the Captain of the Imperial Guards and the emperor from much of the initial explosion, a few stray fiery tongues had singed off much of the hair on the captain and left the right side of his face and his right arm badly burned. But the emperor, though shocked, was unharmed.

The captain dropped the throne, and, wincing with pain, he leaned over the side of the Pagoda and shouted down at the shocked archers.

“Fire at will!”

He cursed himself at the emphasis on absolute discipline he had instilled in the guards so that they focused more on obeying orders than reacting on their own initiative. But it had been so long since the last attempt on the emperor’s life that everyone had been lulled into a false sense of security. He would have to look into improvements in training—assuming he got to keep his own head after this failure.

The archers launched their arrows in a volley. The assassin pulled on the strings of the kite, folded the wings, and banked in a tight arc to get out of the way. The spent bolts fell like black rain from the sky.

Thousands of dancers and spectators merged into the panicked chaos of a screaming and jostling mob.

“I told you this was a bad idea!” Rin looked around frantically for somewhere to hide. He yelped and jumped out of the way of a falling arrow. Beside him, two men lay dead with arrows sticking out of their backs. “I should never have agreed to help you with that lie to your parents about school being closed. Your schemes always end with me in trouble! We’ve got to run!”

“If you run and trip in that crowd, you’re going to get trampled,” said Kuni. “Besides, how can you want to miss this?”

“Oh gods, we’re all going to die!” Another arrow fell and stuck into the ground less than a foot away. A few more people fell down screaming as their bodies were pierced.

“We’re not dead yet.” Kuni dashed into the road and returned with a shield one of the soldiers had dropped.

“Duck!” he yelled, and pulled Rin down with him into a crouch, raising the shield over their heads. An arrow thunked against the shield.

“Lady Rapa and Lady Kana, p-pr-protect me!” muttered Rin with his eyes squeezed tightly shut. “If I survive this, I promise to listen to my mother and never skip school again, and I’ll obey the ancient sages and stay away from honey-tongued friends who lead me astray.…”

But Kuni was already peeking around the shield.

The kite rider jackknifed his legs hard, causing the wings of his kite to flap a few times in rapid succession. The kite pulled straight up, gaining some altitude. The rider pulled the reins, turned around in a tight arc, and came at the Throne Pagoda again.

The emperor, who had recovered from the initial shock, was being escorted down the spiraling stairs. But he was still only halfway to the foot of the Throne Pagoda, caught between the Worlds of Earth and Fire.

“Rénga, please forgive me!” The Captain of the Imperial Guards ducked and lifted the emperor’s body, thrust him over the side of the Pagoda, and dropped him.

The soldiers below had already stretched out a long, stiff piece of cloth. The emperor landed in it, trampolined up and down a few times, but appeared unhurt.

Kuni caught a glimpse of the emperor in the brief moment before he was rushed under the protective shell of overlapping shields. Years of alchemical medicine—taken in the hope of extending his life—had wreaked havoc with his body. Though the emperor was only fifty-five, he looked to be thirty years older. But Kuni was most struck by the old man’s hooded eyes peering out of his wrinkled face, eyes that for a moment had shown surprise and fear.

The sound of the kite diving behind Kuni was like a piece of rough cloth being torn. “Get down!” He pushed Rin to the ground and flopped on top of his friend, pulling the shield above their heads. “Pretend you are a turtle.”

Rin tried to flatten himself against the earth under Kuni. “I wish a ditch would open up so I could crawl into it.”

More flaming tar exploded around the Throne Pagoda. Some struck the top of the shield bunker, and as the sizzling tar oozed into the gaps between the shields, the soldiers beneath cried out in pain but held their positions. At the direction of the officers, the soldiers lifted and sloped their shields in unison to throw off the burning tar, like a crocodile flexing its scales to shake off excess water.

“I think it’s safe now,” said Kuni. He took away the shield and rolled off Rin.

Slowly, Rin sat up and watched his friend without comprehension. Kuni was rolling along the ground as if he was frolicking in the snow—how could Kuni think of playing games at a time like this?

Then he saw the smoke rising from Kuni’s clothes. He yelped and hurried over, helping to extinguish the flames by slapping at Kuni’s voluminous robes with his long sleeves.

“Thanks, Rin,” said Kuni. He sat up and tried to smile, but only managed a wince.

Rin examined Kuni: A few drops of burning oil had landed on his back. Through the smoking holes in the robe, Rin could see that the flesh underneath was raw, charred, and oozing blood.

“Oh gods! Does it hurt?”

“Only a little,” said Kuni.

“If you weren’t on top of me…” Rin swallowed. “Kuni Garu, you’re a real friend.”

“Eh, think nothing of it,” said Kuni. “As Sage Kon Fiji said: One should always—ow!—be ready to stick knives between one’s ribs if that would help a friend.” He tried to put some swagger into this speech but the pain made his voice unsteady. “See, Master Loing did teach me something.”

“That’s the part you remember? But that wasn’t Kon Fiji. You’re quoting from a bandit debating Kon Fiji.”

“Who says bandits don’t have virtues too?”

The sound of flapping wings interrupted them. The boys looked up. Slowly, gracefully, like an albatross turning over the sea, the kite flapped its wings, rose, turned around in a large circle, and began a third bombing run toward the Throne Pagoda. The rider was clearly tiring and could not gain as much altitude this time. The kite was very close to the ground.

A few of the archers managed to shoot holes in the wings of the stringless kite, and a few of the arrows even struck the rider, though his thick leather armor seemed to be reinforced in some manner, and the arrows stuck only briefly in the leather before falling off harmlessly.

Again, he folded the wings of his craft and accelerated toward the Throne Pagoda like a diving kingfisher.

The archers continued to shoot at the assassin, but he ignored the hailstorm of arrows and held his course. Flaming missiles exploded against the sides of the Throne Pagoda. Within seconds, the silk-andbamboo construction turned into a tower of fire.

But the emperor was now safely ensconced under the pavises of the shieldmen, and with every passing moment, more archers gathered around the emperor’s position. The rider could see that his prize was out of reach.

Instead of another bombing attempt, the kite rider turned his machine to the south, away from the Procession, and kicked hard with his dwindling strength to gain some altitude.

“He’s heading to Zudi,” Rin said. “You think anyone we know back home helped him?”

Kuni shook his head. When the kite had passed directly over him and Rin, it had temporarily blotted out the glare of the sun. He had seen that the rider was a young man, not even thirty. He had the dark skin and long limbs common to the men of Haan, up north. For a fraction of a second, the rider, looking down, had locked gazes with Kuni, and Kuni’s heart thrilled with the fervent passion and purposeful intensity in those bright-green eyes.

“He made the emperor afraid,” Kuni said, as if to himself. “The emperor is just a man, after all.” A wide smile broke on his face.

Before Rin could shush his friend again, great black shadows covered them. The boys looked up and saw yet more reasons for the kite rider’s retreat.

Six graceful airships, each about three hundred feet long, the pride of the Imperial air force, drifted overhead. The airships had been at the head of the Imperial Procession, both to scout ahead and to impress the spectators. It had taken a while before the oarsmen could turn the ships around to bring them to the emperor’s aid.

The stringless kite grew smaller and smaller. The airships lumbered after the escaping assassin, their great feathered oars beating the air like the wings of fat geese struggling to lift off. The rider was already too far for the airships’ archers and stringed battle kites. They would not reach the city of Zudi before the nimble man landed and disappeared into its alleys.

The emperor, huddled in the dim shadows of the shield bunker, was furious, but he retained a calm mien. This was not the first assassination attempt, and it would not be the last; only this one had come closest to succeeding.

As he gave his order, his voice was emotionless and implacable.

“Find that man. Even if you have to tear apart every house in Zudi and burn down the estates of all the nobles in Haan, bring him before me.”

Excerpted from The Grace of Kings by Ken Liu. Copyright © 2015. Published By Saga Press, an imprint of Simon & Schuster. Used by permission of the publisher. Not for reprint without permission.